MY MOTHER’S TONGUE

My Mother’s Tongue is a solo show that exhibited at Bus Projects in October 2022 and then at Singapore Art Museum in October 2024 as part of the group show Lost & Found: Embodied Archives.

Artwork details:

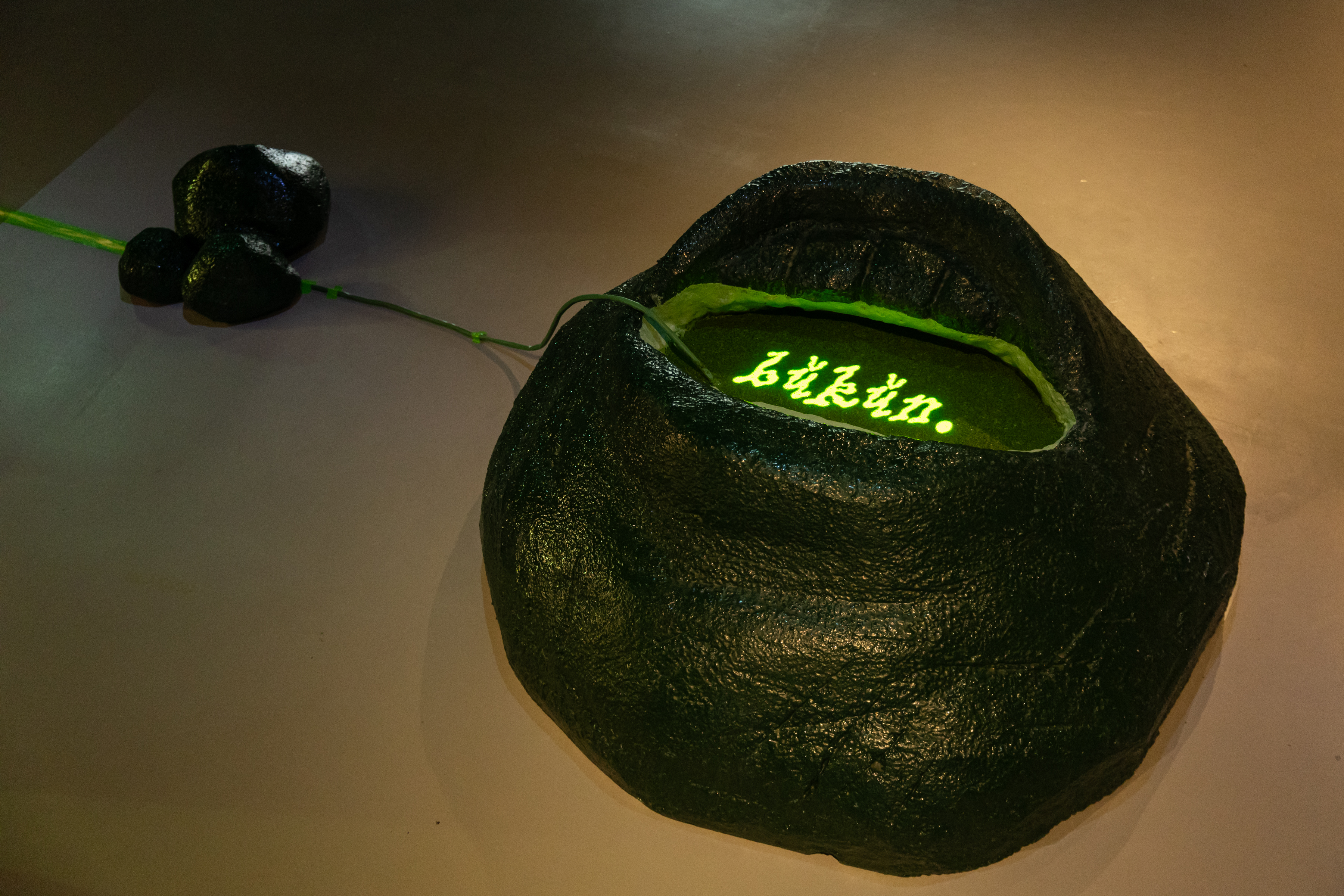

Foam, epoxy resin, fibreglass mat, sand, water-based epoxy, paint, mica pigment, green food dye, titanium dioxide, water, miniature water pump, duckweed, projection.

Pond carving assisted by sculptor Annika Lee.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, detail view, Singapore Art Museum. Photo by Singapore Art Museum.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, installation view, Singapore Art Museum. Photo by Singapore Art Museum.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, installation view, Singapore Art Museum. Photo by Singapore Art Museum.

Since 2019 I have been learning Bukar - an Indigenous language from Borneo that is also my mother’s native tongue. This is a considerable undertaking. Bukar is spoken only by Bidayǔh people who live in villages at the base of Bung Sadung, a mountain range two hours from Kuching, Sarawak. With very few resources available to me in so-called Australia, I have been relying on Whatsapp chats with my extended family, phone calls with my mother and a single Bukar-English dictionary sent to me by my cousin. I also have a handful of books written in Bukar that recount Bidayǔh origin stories, such as why we use omen birds, why incest is bad, or why you have to ask permission from the land before building a longhouse or making a padi field.

This is a map of the Bung Sadung mountain range and its surrounding villages. The highest elevation is 400 metres. Our ancestors are said to have immigrated from what is now Indonesian Borneo, escaping inter-tribal warfare, and settled deep in the mountain range. Over time they moved out and founded villages. This is the heart of Bukar language - an 11 kilometre diameter ring of villages surrounding the Bung Sadung mountain range. At the last census in 2000, over 20 years ago, there were approximately 49 000 Bukar speakers recorded.

This work features a pond carved in the shape of my mother’s mouth. Projected into the pond is a passage from the very first book I ever completed cover-to-cover in Bukar called Antung dengan Awan, an accomplishment I am very proud of. Antung dengan Awan is an epic, multi-part tale about a brother and sister who committed incest and were banished to a land where there were only rocks. After bearing many children, the parents die and their final wishes are to be buried. On top of their graves the children were told to clear the land and make a padi field, but they were told they must not visit the land for four nights. The English translation of the next part of the story goes like this:

After four nights, Antung and Awan’s children went to visit the padi field. When they got there, they saw that all kinds of plants were living in the padi field. Not one of them knew the names of these plants and what use they had to human beings. When they returned home they were in a commotion, asking each other what were these strange seedlings that were now living on their padi field. Labu* heard her brothers and sisters talking and said “If you don’t know what these plants are, take me there so that I can see them. Maybe I will know their names and what use they have to humans.”

When her brothers and sisters heard this, they carried Labu on their shoulders to the padi field. When they got there, the strange plants were still growing. But Labu knew all of the plants’ names and how humans should use them. They took Labu to their mother’s grave and she said to her brothers and sisters “Oh, look, our mother has transformed into all these plants. This is rice, corn, barley and sesame. This is tapioca, yam, potato, sweet potato, winter melon, cucumber, pumpkin, and many other plants too.”

Labu then went on to explain that all of these plants could be eaten and used to sustain human life. The barley plant is the last to ripen in the padi field, so people plant it to use as a fence. When ripened, the barley grain is good to use to make wine and porridge. The other plants were good to use as a vegetable - like cucumber, pumpkin, loofah, winter melon and spinach.

Spinach, said Labu, was good to cook with cucumber vine leaves when the leaves are still young. Chilli is good to eat when the leaves are still immature✝, and the fruit is good to use in fermentation. As for winter melon - the fruit is good to use as a vegetable. And when the gourd is still young you can eat it, but when the fruit is old you can use it as a vessel in ceremony.

*Labu is the fourth child of brother and sister Antung and Awan. She must be carried around because she was born without arms and legs. She is said to be very beautiful and intelligent, knowing how to speak very early in life. Later she is fought over by two men who start a war for her love.

✝I looked this up - you can eat the leaves when they are young but they must be cooked first. They are said to be delicious.

My mother chose not to teach us Bukar. She felt that, in a global economy, this language had no value and we were better off speaking English. But, while relearning Bukar, I have wondered what I may have inherited from her anyway. Even though I was born far from my mother’s ancestral lands, does my mouth know how to make the sounds already? Like Labu, on some level, was I born already knowing the names of things? Does my tongue feel at home when I speak Bukar?

Bukar has hundreds of terms for activities that speak to a daily rhythm of moving through the jungle and working intimately with plants. For me, learning these untranslatable and increasingly rarely used words conjures up rich images of pre-colonial Bidayǔh life. Returning to Sarawak and taking in the overwhelming green of the mountainous jungles on Bung Sadung, I believe that Bukar language literally arose from this landscape. Words grew up from the ground, floated downstream in rivers, or shone directly from the equatorial sun onto the wet and muddy forest floor. I believe that the Bang Sadung mountain range is sentient, and gifted Bidayǔh people plants, animals and the words to describe them. Our ancestors picked those words up and used their mouths to pass them on - so that we all may know the world better.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, installation view, Bus Projects, VIC. Photo by Christo Crocker.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, detail, Bus Projects, VIC. Photo by Christo Crocker.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, detail, Bus Projects, VIC. Photo by Christo Crocker.

My mother’s tongue, 2022, installation view, Bus Projects, VIC. Photo by Christo Crocker.

I live and work on the lands of the Awabakal and Worimi people.

This sovereign land was never ceded.

The land I live on always was and always will be Aboriginal land.